One of the functions of a local trail association is to undertake planning exercises. Members’ input against the backdrop of local opportunities and challenges give rise to trail development, maintenance, signage, and fundraising strategies.

The pandemic has led me to think about the state of our trail networks during a crisis. What are the consequences of a crisis on a trail network? What can we do to help strengthen them for the future? Below are some thoughts worth considering for your association:

Multi-Nodal Stacked-Loop Networks

Systems that are centered around multiple hubs with trails of increasing difficulty propagating from those nodes have multiple benefits. During normal times they help to spread out users, maximize return on investment, and manage liability. During a crisis these benefits are heightened and we see some new ones.

Natural disasters such as forest fires, landslides or earthquakes can sometimes sever primary access routes or roads. Multiple options to access the network can prevent people from being cut off should a disaster strike suddenly. It also provides multiple options for search and rescue operations and wildfire response.

With current capacity in hospitals limited and people taking it easy, having multiple points to access a variety of easy and intermediate trails will help to spread people out and limit conflict. Many new users are accessing the trails now that other options are unavailable. Additional access points can help increase capacity, while the stacked loop pattern can help new visitors make better decisions about which trails they use.

An extension of the stacked loop system quickly becoming more relevant is integration with active transportation infrastructure. The advent of Ebikes and the growing popularity of trail recreation in general means that we are reaching a critical mass where the expense of this infrastructure becomes worthwhile. It is easy to imagine a future crisis that hits transportation or energy issues that could be addressed by integrating our trail systems with active transportation planning.

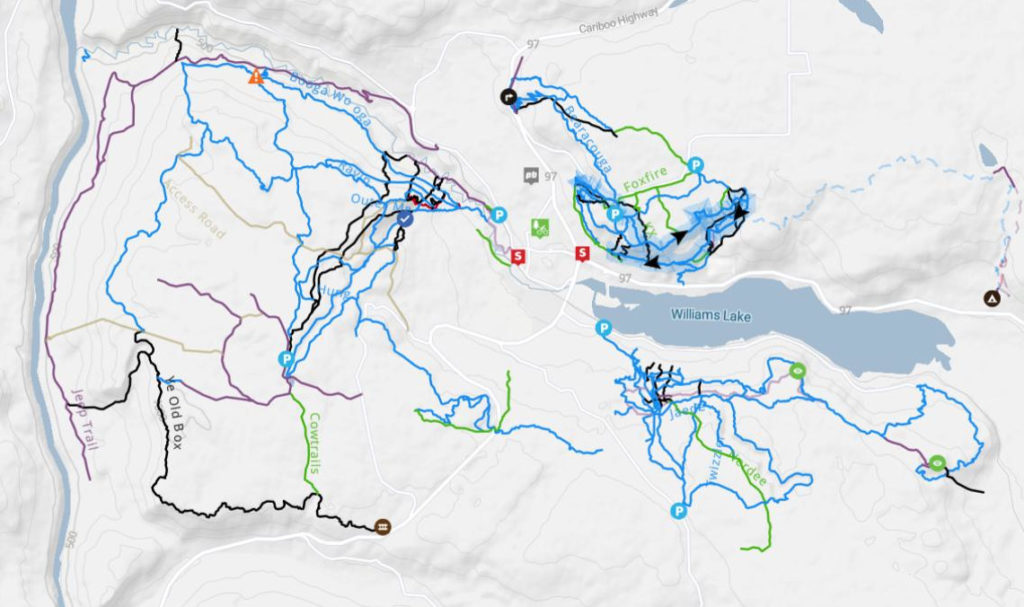

Williams Lake is a good example of a real-life stacked loop network. With multiple zones and multiple entry ways into each area, access is dispersed and many options are available. Many of the trails that connect to the main areas are moderate difficulty, with the more difficult trails a bit harder to access. In addition, you can see the work of the trail association with the trail that leads from one of the local First Nation campgrounds into the network.

Trained and Empowered Builders

Sudden drops in capacity for trail association trail crews, municipal trail staff or others are bound to occur for a variety of reasons. Having trained and empowered volunteers who understand trail assessment, maintenance, planning, and construction can help to alleviate this. Trained and empowered locals can take up some of the maintenance work needed to manage liability issues in the short term and can help with larger or longer duration drops in capacity by taking ownership over trails.

Many tasks can easily be taken care of by volunteers, with varying levels of experience required.

Assessment and Trail Reports

Probably one of the easiest to start doing right now. Enlist volunteers to assess trails for damage and provide trail reports. This gives the association a high level view of what’s happening on the trails and makes it far easier to prioritize projects.

Design and Field Investigation of New Trail

During a crisis is a great time to start thinking about new opportunities if the time is right. Many communities have some very talented individuals who – given recommendations not to take undue risks – may not be building trails. Sending those individuals out to investigate new opportunities might pay dividends in the future.

TTF Inspection

Liability is a large concern for many associations and land managers. Sending out volunteers on the regular to inspect and address technical trail feature issues can help prevent any accidents or lawsuits due to disrepair.

Corridor Clearing

One of the easiest maintenance jobs, clearing the corridor helps to improve visibility and overall experience and reduces the misuse of trails. Even better is that these projects can be done alone* and are very low risk.

Trail Tread Maintenance, including drainage features, outslope, and tread hardening

Lastly, work on the trail tread itself can also be easily accomplished by volunteers. You’ll need to ensure that they’ve had some training on the best practices of each type of maintenance before starting out as you don’t want to have to redo the work of these labour intensive jobs.

Physically Durable Trails

A careful balance between social, physical, and managerial sustainability is an important indicator of whether a trail network matches the community. Too much emphasis in any one direction may mean shortcomings in other areas.

That being said, a majority of a trail network being durable and easy to maintain will be a significant benefit during a crisis. Blue and green trails are perfect candidates for additional durability, given that

the layout associated with high durability (lower average grades and careful speed management) don’t interfere with what people expect out of those styles of trails. Multiplying this benefit is also that more people tend to use these trails and that the focus on risk-aversion during a crisis may lead to them being even more important.

Maximizing the durability of black and double black diamond trails – while retaining the character of the trail – can be done as well. Careful line choice coupled with durable rock armouring or slabs can significantly limit erosion. In Squamish, many of our most difficult, steepest trails are incredibly durable as they maximize rock slabs and armouring. There will be only minor issues to address as we resume riding them.

Community Core

Group rides, trail builds, teaching clinics, barrier free and inclusive events – we typically think of these as a service provided by associations for riders, sometimes as a benefit for their membership or to encourage donations. These also help to instill a strong sense of community spirit, which is a critical resource during a time of crisis. Trail closures, usage restrictions, calls for volunteer support – the way a community responds to these messages is influenced in part by how strongly people identify with that association. Building social capital not only pays off in periods of calm, but also during conflict and crisis.

Strong Stakeholder and Land Manager Relationships

Representation of the community to outside stakeholders and land management agencies is probably one of the key avenues in which advocacy work is completed. Trail access, funding agreements, and cooperative programming are almost always built on a foundation of agreements – written and verbal – between the local association and other entities. While written agreements are important, the social capital built by ongoing work together and accomplishing goals adds tremendous value when it comes time to act as a community together in a time of crisis.

An association with longstanding community and government ties will be in a better position to advise on the best course of action with respect to how disaster response proceeds. Indeed, agencies that don’t have in depth knowledge on the nuance of trails and usage will appreciate being provided guidance.

When planning trail development, we’re inclined to envision how things will be under good circumstances. Adding to that mix the ways we might use them under any number of negative situations is a useful exercise to balance that approach. In the end, a well considered strategy will maximize the available opportunities while also ensuring a sustainable system of trails that can be depended upon during times of need.